A publication in Science Immunology, titled ‘FOXP3 exon 2 controls Treg stability and autoimmunity’, explores how Foxp3 gene might function. The paper can be accessed here.

Background

The regulatory T cells (Tregs) are an important immune cell that suppresses other immune cells. They are important for suppressing activation of immune cells against our own body. A gene called Foxp3 is critical for the function and development of Tregs. Mutations in Foxp3 can manifest in auto-immune diseases in humans (The disease is called IPEX).

In humans, Foxp3 can exist as isoforms that either contain the full length (FL) of the mRNA transcript, or ones that lack the exon 2 (hereafter referred to as Foxp3 ∆E2 isoform). Patients who suffer from autoimmune diseases express a lot of the Foxp3 ∆E2 isoform. This suggests that the exon 2 is important for Treg function, but it is unclear how. The authors study what exon 2 of the Foxp3 gene does.

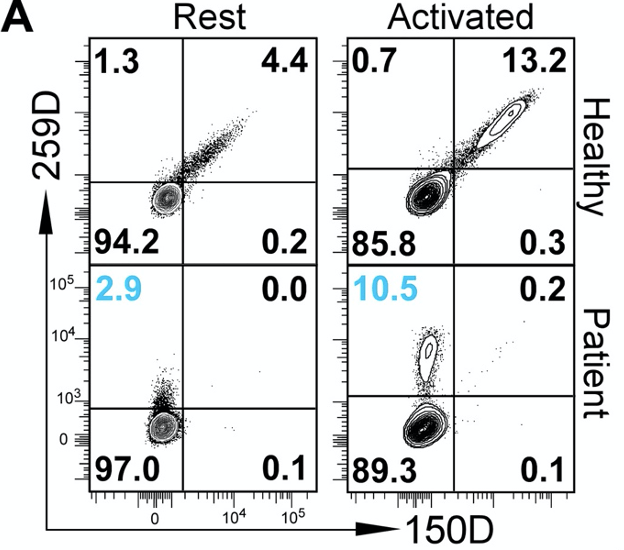

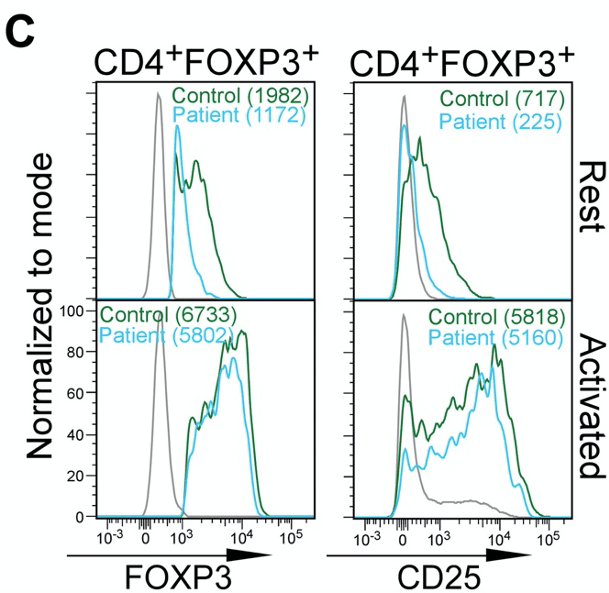

Figure 1 shows that IPEX patients have Foxp3 ∆E2 isoforms. Their Tregs can still become activated despite lacking exon 2.

The authors sought to identify whether ∆E2 isoforms are found in IPEX patients. To do this, they used two different antibodies: 150D antibody that binds to the portion of the Foxp3 gene encoded by exon 2; and 259D antibody, which binds to the portion of Foxp3 protein that is encoded by other exons. Using these two antibodies, they saw that IPEX patients have Tregs that express a lot of ∆E2 Foxp3 proteins. The abundance of such Tregs increase upon their activation, showing that these cells are still competent to respond to activation signals downstream of CD3 receptors.

The authors also observe that the abundance of Foxp3 protein and CD25 (an indicator/marker for activation status of Tregs) is not dissimilar between Tregs of “Control” and “Patients”.

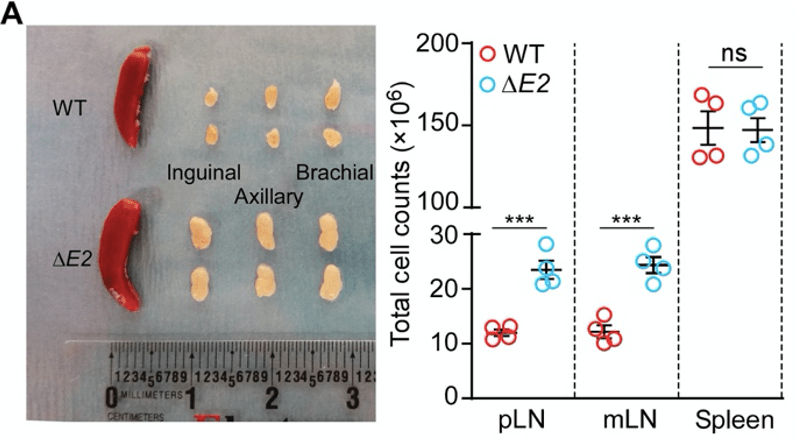

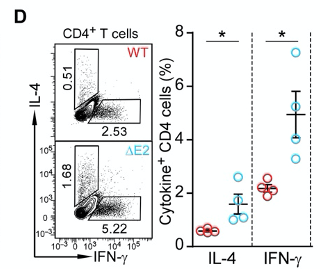

Figure 2 shows that lack of Foxp3 exon 2 causes systemic inflammation

The authors produced mutant mice that lack exon 2 of the Foxp3 gene (these will be referred to as ∆E2 mice for convenience). In comparison to the healthy wild-type (WT) mice, the lymph nodes of the ∆E2 mice are enlarged. In parallel, the lymph nodes are packed with more cells. Together, these are indications of inflammation that is ongoing in the lymph nodes.

Indeed, when they profiled the production of cytokines in T helper cells, they observed higher production of intereferon gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin 4 (IL-4) in ∆E2 mice.

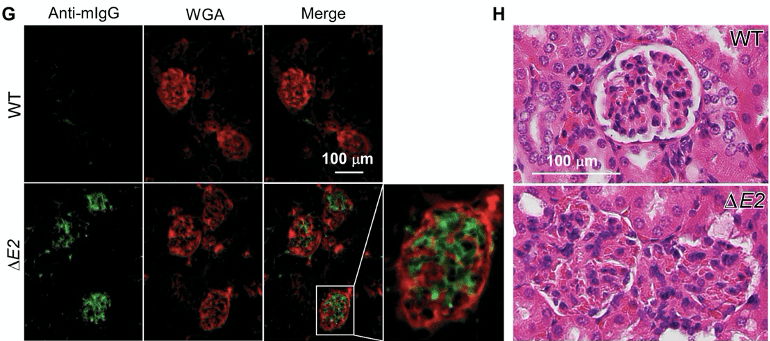

Figure 3 shows that lack of exon 2 causes autoimmunity

Autoimmunity is a reaction of immune cells to their own body. The authors show that this occurs in ∆E2 mice by histological staining of tissues.

The authors visualised presence of IgG antibodies (green) that are bound to their own kidney (red) in ∆E2 mice. The auto-reactive binding of IgG antibodies to the kidney is associated with the destruction of the glomeruli.

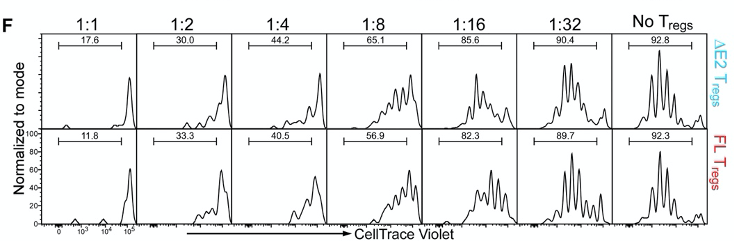

Figure 4 shows that Tregs of ∆E2 mice are not dissimilar to that of WT mice, and they possess the same suppressive capacity

The authors co-culture Tregs and T helper cells at specific ratios as seen in figure 4F. The idea of this experiment is that functional Tregs will suppress the proliferation of T helper cells. Cells are dyed with CellTrace Violet, and this dye becomes diluted every time a cell divides. However, the authors did not see any difference in the dilution of the dye between ∆E2 Tregs and WT Tregs.

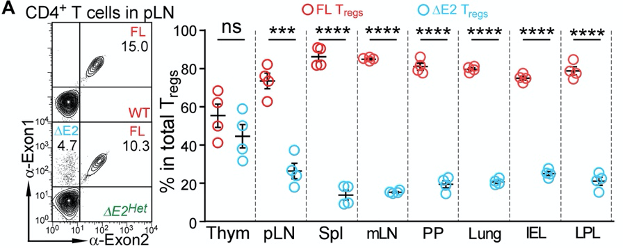

Figure 5 shows ∆E2 Tregs unable to establish presence in peripheral tissues as efficiently as WT Tregs.

The authors profiled the abundance of ∆E2 Tregs in mice that have both ∆E2 Tregs and WT Tregs (A mouse has 2 copies of the Foxp3 gene. One of them is an ∆E2 allele, and the other is an WT allele. Such a mouse is referred to as being heterozygous). Peripheral tissues, such as the lymph nodes, spleen, lungs, and the intestines were largely occupied by WT Tregs, and not ∆E2 Tregs.

Overall, this suggests that whilst ∆E2 Tregs are functional, they’re unable to establish presence at peripheral sites. This could underly the auto-immune pathologies as Tregs cannot enter peripheral tissues to suppress other immune cells.

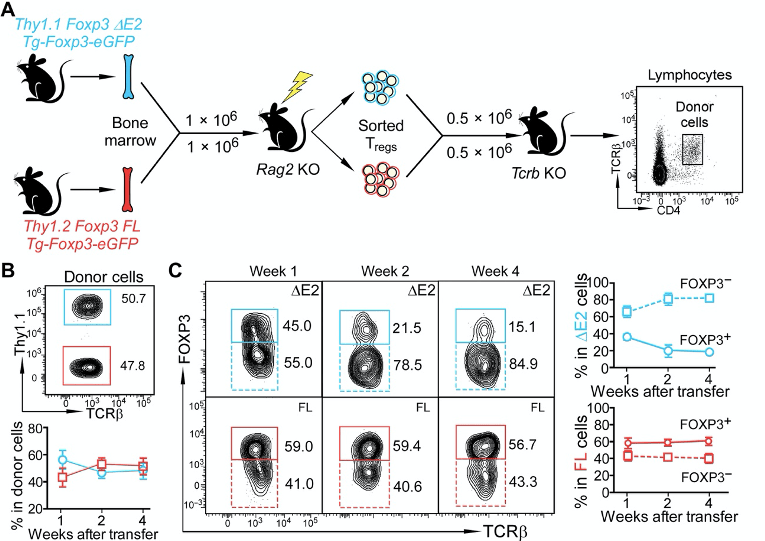

Figure 6 suggests that the Treg fate of ∆E2 Tregs is unstable

The authors set out a goal to understand how ∆E2 Tregs might affect the Treg fate. In other words, could they steadily lose Foxp3 expression and become less Treg-like? They do this by using an adoptive transfer of ∆E2 Tregs and WT Tregs to recipient mice. I’m not sure why they address this question in this way. They could simply just perform a lineage tracing system. This would enable them to assess how cells that were once a Treg may or may not have lost Foxp3 expression.

In any case, they authors make a point that if they follow the Tregs over long term (panel B and C), the ∆E2 Tregs start becoming more Foxp3-negative. This suggests that lack of exon 2 might cause instability of the Treg fate.

The paper is then wrapped up with a bulk RNA sequencing study of ∆E2 Tregs vs WT Tregs. The results show that the ∆E2 Tregs express more cytokines, suggesting that they have adopted a more effector-like phenotype.

All in all, this is a very confusing paper that gives mixed messages. The in vitro systems show that ∆E2 Tregs are not dysfunctional. But, the last couple of figures seem to then suggest that actually ∆E2 Tregs are dysfunctional. What could have caused the auto-immune disorders in ∆E2 mice? I lean closer towards believing that the ∆E2 Tregs are functional, but they are less able to establish presence in the peripheral tissues.