In this post, we discuss a publication in Nature Immunology, titled ‘Glucocorticoid signaling and regulatory T cells cooperate to maintain the hair-follicle stem-cell niche’. The paper can be accessed here.

This paper examines the role of regulatory T cells (Tregs). Tregs are a subset of immune cells that are known for its ability to control and suppress other immune cells. Their function is extremely important for keeping immune cells in check so that we do not develop allergy, or autoimmunity.

In recent years, scientists have discovered that the role of Tregs is not limited to their immune regulation. In the skin, it has been shown that they regulate the hair follicle stem cells, cells which are responsible for hair growth. The paper today explores how Tregs respond to steroid hormones and regulate hair growth.

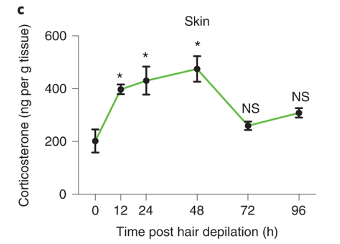

Figure 1 provides suggestive evidence that Tregs might utilise steroid hormone to regulate hair growth.

First, the authors remove the mice’s hair. The simple removal, called depilation, is known to stimulate the growth of hair. Shortly after depilation, the abundance of a steroid hormone (corticosterone) increases in the skin.

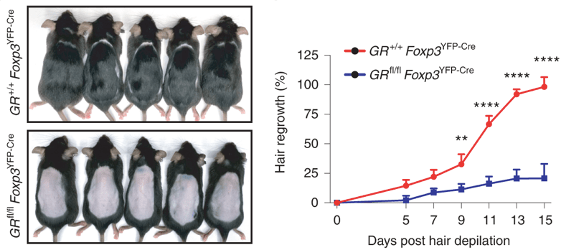

It turns out, that if Tregs lack a receptor for corticosterone (receptor is abbreviated as GR), mice are unable to regrow hair after depilation (bottom picture). For convenience, mice that with Tregs lacking will be abbreviated as GR-KO.

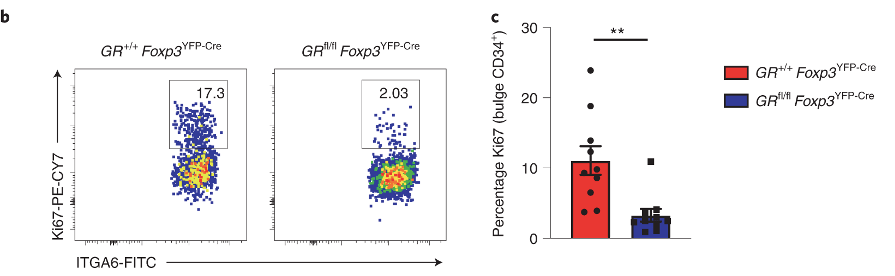

Figure 2 confirms defective hair growth when Tregs lack glucocorticoid receptors.

The hair follicle stem cells are the cells that divide and differentiate to produce the cells of the hair. The authors looked at how many cells are dividing (panel b) after depilation, and found that there is significantly less stem cell proliferation (panel c) in GR-KO mice.

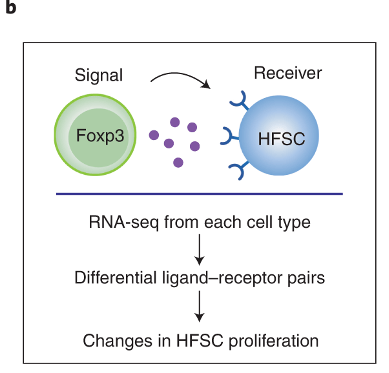

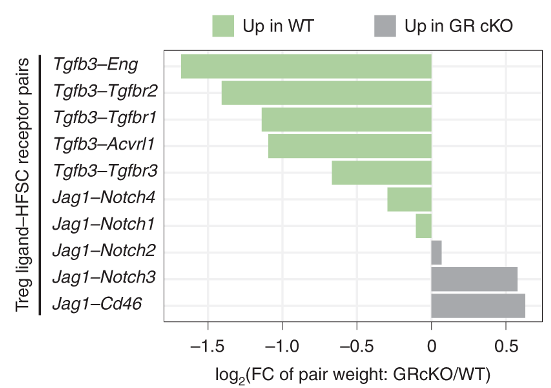

Figure 3 uses RNA-sequencing data to predict how Tregs and HFSCs might be interacting with each other

The authors sequenced the RNA obtained from Tregs and HFSCs after depilation. This allows them to find what ligand-receptor pairs they might have used to interact with one another. The process by which they do this involves looking at known database of ligand-receptor pairs. If any of those genes are differentially expressed in either the Tregs or the HFSCs, then we can say that the strength of interaction via the ligand-receptor pairs may have changed.

By using this approach, they identify that TGFb3 signalling may be important for Treg-HFSC interaction.

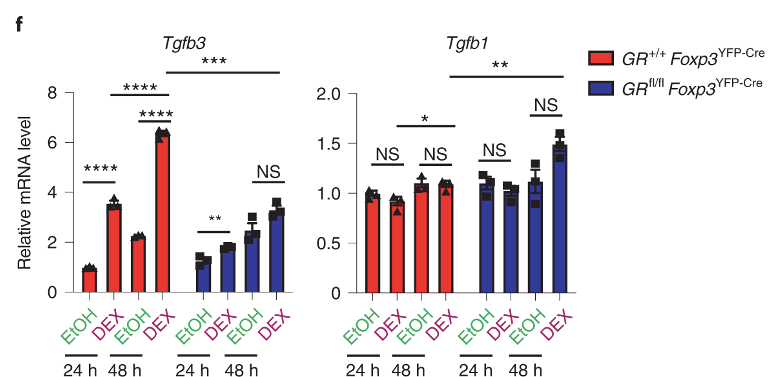

They confirm that the expression of Tgfb3 increases in Tregs upon depilation (DEX vs EtOH, panel f). The same occurs in GR-KO mice, but at much lower magnitude. For the most part, Tgfb1 can be ignored.

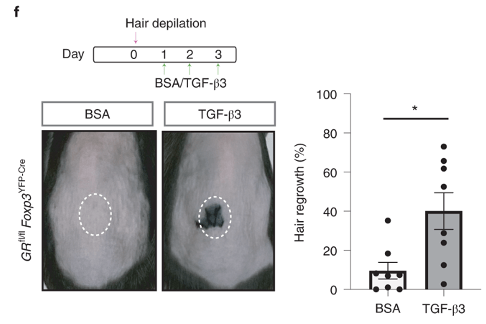

Figure 5 shows TGFb3 signalling is required for hair growth

The authors injected beads that are soaked with TGFb3 after depilation of GR-KO mice. In BSA control mice, hair is unable to grow as a result of Treg defect. But, the beads are able to rescue hair growth. This provides concrete evidence that Tgfb3 is downstream of Tregs and regulates hair growth.

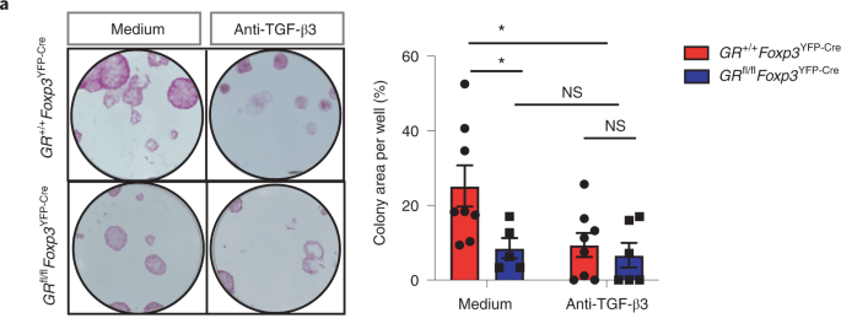

Figure 6 shows that HFSCs are less functional in GR-KO mice

The authors purified HFSCs and grew them in the presence of purified Tregs obtained from either GR-KO mice or wild-type mice. The result is shown above (panel a).

Note that there is a sharp decline in colony formation (functional readout for HFSC growth) in GR-KO mice (medium). But, between medium vs anti-TGFb3 of GR-KO mice (blue), there is no difference. This suggests that HFSCs are unresponsive to TGFb3 in GR-KO mice.

Why is this so? Could HFSCs express lower level of TGFb3 receptor in GR-KO mice? We do not know. The expression level of TGFb3 receptors was not shown anywhere in the publication.

Overall, the publication shows evidence that Tregs utilise glucocorticoid receptors. The receptor is important for Tregs to regulate HFSC growth. Whether the regulation occurs via TGFb3 as the authors suggest is not fully supported.